Chesterfield's Role In the Battle of Bennington

In preparation for war, the NH Assembly and Council passed The Militia Act in September 1776. Towns were required to make two lists or classes of militia. A training band included all able- bodied men ages 16 to 50. An alarm list included all males ages 16 to 65 who were not in the training band. Those exempt from the lists were "Negroes, Mulattoes, Indians", certain public officials, and those engaged in approved jobs. Both lists were organized into companies and regiments which, in part or in whole, were required to respond when duty called. The alarm list was held in reserve only to be called up in an emergency. However, if the occasion demanded the establishment of a town's military defense, everyone was required to take “watch duty”. All the men had to provide arms and equipment at their own expense. If unable, the town had to provide the needed provisions. The necessary supplies included a firearm, ammunition, cutting sword or hatchet, knapsack, a quart (or larger) canteen, and a blanket. Each Town also had to provide a certain number of spades or shovels, pickaxes, and hoes. Chesterfield readily complied.

Chesterfield's militia rallied twice to help defend New York's Fort Ticonderoga, a strategically located fort that housed valuable artillery. The first call to duty was in May 1777, but proved to be a false alarm. However, the troops were barely back from that expedition when they were called out again to defend the fort. The call unfortunately came too late. Most of the men hadn’t marched far, before learning the Fort had fallen to General Burgoyne's British forces on July 6, 1777. The troops returned home after being away only 2 to 13 days.

British General Burgoyne's key plan was to isolate New England from the rest of the colonies by controlling the Hudson River Valley, capturing Albany, crossing the Green Mountains, and securing Brattleboro before returning to Albany. For two months he had successfully led his army southward from Canada. However, in August 1777, he found himself in desperate need of provisions, wagons, cattle, and horses. Burgoyne dispatched a force to seize horses and supplies believed to be stockpiled in Bennington.

The knowledge that a significant British regular army force, which also consisted of Indian, Hessian, and Loyalists, was successfully moving southward through NY alarmed the colonists, especially when many remembered the horrors of the French and Indian Wars. The NH Militia was called out and divided into two brigades. Militias from the area around Chesterfield were assigned to General Stark. One company was under the command of Chesterfield's Capt. Kimball Carlton. Carlton's company consisted of 61 men, 21 were from Chesterfield. He readied his men in Westmoreland and marched from there to join Stark on July 22nd.

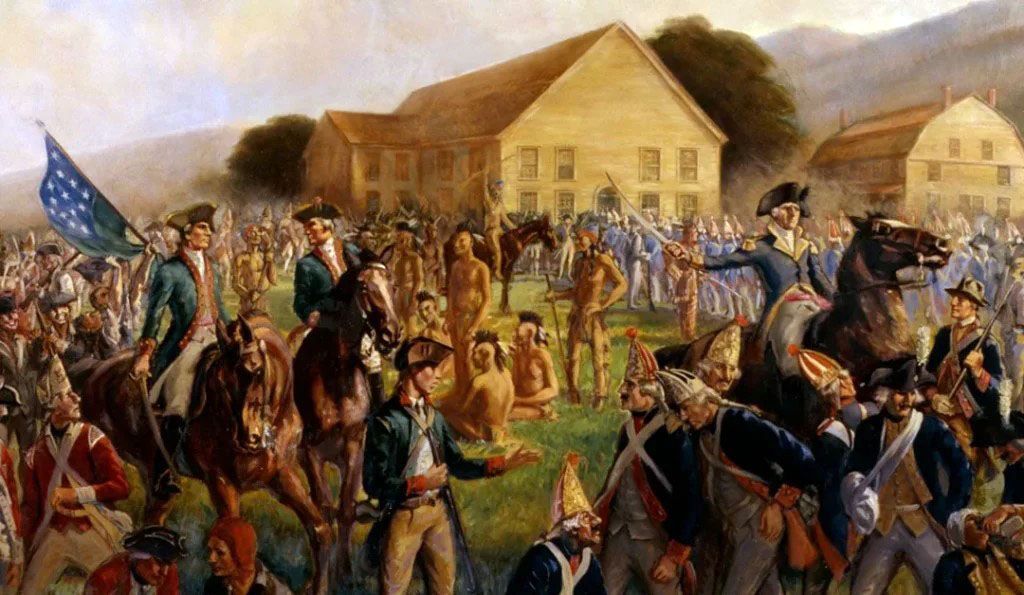

Stark gathered his troops in Manchester, VT and engaged the British forces in Walloomsac, NY, about ten miles from Bennington on Aug 14th - 16th. The American militia, despite being outnumbered and facing experienced German troops, achieved a decisive victory in the two-day long conflict. The British suffered heavy casualties and the loss of valuable supplies and horses. This defeat significantly weakened Burgoyne's army and contributed to his eventual surrender at Saratoga two months later. The American victory also boosted morale and encouraged further support for the Revolution.

According to The History of Chesterfield by Randall, a number of Chesterfield men were engaged in this battle as "independent volunteers", although no evidence has been found of any applying for compensation from the NH Legislation. One such person was John Pierce an ardent patriot and father of Ezekiel Pierce, builder of the present-day Stone House Tavern Museum. According to Pierce family history, John was a cooper in the French and Indian Wars. At the beginning of the Revolution, he was made captain of a company of men raised around Chesterfield.

Pierce's involvement in the battle started with him and his two lieutenants moving ahead of the company. As they neared the British forces, they found themselves between a company of Hessians who were bathing in a stream, and the main body of the British. Carefully crawling upon the bathers, who had stacked their arms, they separated and represented themselves as three companies. Pierce called upon the Hessians to surrender, which they did, and he marched them as prisoners into the American lines. For this he earned the local title of “The Hessian”.*

The roar of the cannons at the Battle of Bennington was distinctly heard in Chesterfield and other neighboring towns. These discordant sounds caused a great deal of fear among those left behind. Only two of Capt. Carlton’s men were killed, Pvt. John Ranstead and Chesterfield’s own Fifer Benoni Tisdale. Neither died in the actual battle, but in an ambush by Tories in Greenbush, NY while trying to secure some cattle. Most of Carlton’s remaining men served for two months and two days or until Sept. 24th. Their pay was 4 pounds, 10 shillings per month.

(*The History of Chesterfield by Randall does not list John Pierce on any of Chesterfield's Revolutionary War militia rosters, but this information is incomplete. Randall does confirm his nickname.)