Sarah Josepha Hale

The present-day Thanksgiving holiday celebration often includes football, Macy’s Parade, Black Friday Sales, and overeating with family and friends. This feast gathering has been a staple for New Englanders since 1621. However, it was not always embraced by the rest of the country. In fact, making it a nationwide celebration was the work of one very determined woman from New Hampshire, Sarah Josepha Hale.

In the past there were occasional national Thanksgiving celebrations decreed by presidents. In 1789, George Washington made a Day of Thanksgiving the first ever Presidential Proclamation. In March 1815, James Madison declared a Day of Thanksgiving following the end of the War of 1812. These two celebrations were both only for a single day. Actually, there were no federal holidays until 1870. Holidays before then were determined locally with the 4th of July being the most universally celebrated day.

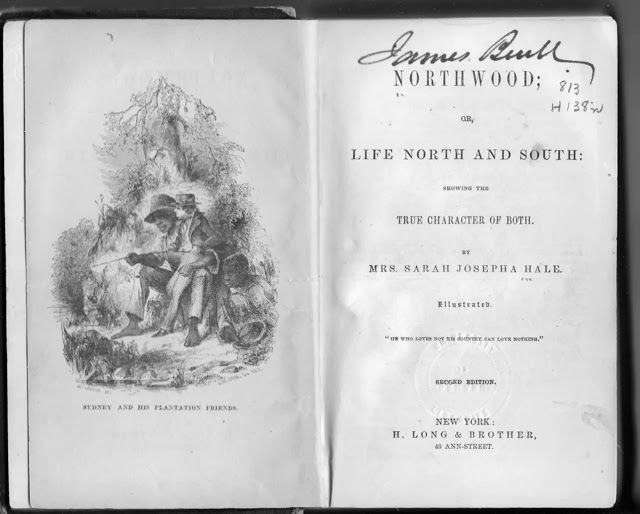

Thanksgiving was a New York and New England tradition that Sarah Josepha Hale loved. This holiday played a major role in her popular 1827 novel “Northwood: Life North and South”. An entire chapter is dedicated to the practices and description of a traditional New England Thanksgiving:

“The table, covered with a damask cloth…intended for the whole household, every child having a seat on this occasion and the more the better, it being considered an honor for a man to sit down to his Thanksgiving supper surrounded by a large family… The roasted turkey took precedence on this occasion, being placed at the head of the table; and well did it become its lordly station, sending forth the rich odor of its savory stuffing.” After mentioning other meats and plenty of vegetables, she concludes with “the celebrated pumpkin pie and indispensable part of the good and true Yankee Thanksgiving.”

Through her descriptions in “Northwood: Life North and South” and a short 1829 story called the “Thanksgiving of the Heart”, Hale revealed what she believed was the essence of the holiday. It was a time when family and friends came together despite their differences and sat in peace during a wonderful meal. She believed that if a community could do it, so could the nation, especially when it was slowly being torn apart by the issue of slavery.

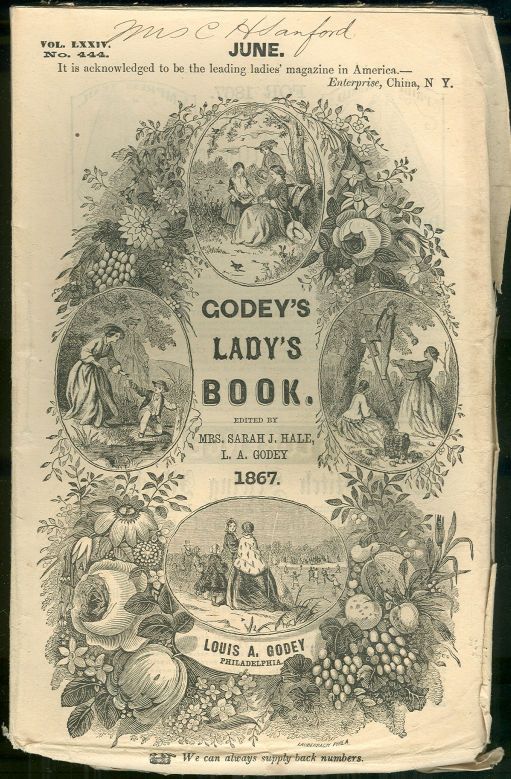

In 1837, Hale became the editor of the "Godey’s Lady’s Book" which reached over 100,000 subscribers. Her work with the magazine made her one of the most influential voices of the 19th Century. Through persuasive writing, Hale used her columns to promote numerous causes, including having a national Thanksgiving holiday. Over the next two decades, her articles stressed the moral, social, and even the political benefits of the celebration. Hale thought the end of November was the best time for the occasion, because the elections would be over, the harvest was in, and there could be peace at the table. She also promoted Thanksgiving by encouraging other publications to do the same and incorporating it into her poems and short stories.

In addition, Hale started a personal letter writing campaign to prominent officials trying to persuade them to promote a Thanksgiving holiday. Her original goal was to persuade the governors of each state to agree on celebrating it on the same day each year. It was partially successful because in 1846 at least 21 of the 29 states did celebrate Thanksgiving, but not all on the same day. However, not all governors were supportive. Virginia's Governor Henry Wise, who was a slave holder, heatedly informed Hale that his state would not be signing on to the “theatrical national claptrap of Thanksgiving.” The holiday was “aiding the antislavery movement,” he complained, as Northern ministers used Thanksgiving as an opportunity to preach against slavery.

Hale wrote to presidents too. Zachary Taylor, Millard Filmore, Franklin Pierce, and James Buchanan all declined her request. They each responded that holiday declarations needed to be left up to the states, and it was not acceptable for a president to dictate a Thanksgiving holiday. Franklin Pierce's response was more pointed, he perceived "serious objections”. He had reason, for in 1856, not only Virginia, but much of the South viewed the celebration as a “Yankee Holiday".

By 1860, it was obvious the country was in great peril. In September, Hale wrote the following in the "Godey’s Lady’s Book": “the last Thursday in November…If all the States and Territories hold their thanksgiving on that day, there will be a complete moral and social reunion of the people of America. Would not this be a good omen for the perpetual political union of the states?”

Finally in 1863, at the age of 74, she turned her message from persuasion to forcefulness. With the Civil War in its 3rd year, in Sept 1863, she wrote to Secretary of the State, William Seward, a New Yorker, a letter urging him to convince Lincoln to declare a national Thanksgiving holiday. At the same time, she wrote Lincoln a similar long, compelling letter in which she demanded immediate action. “It now needs National recognition and authoritative fixation, only, to become permanently, an American Custom and Institution.” (letter to Lincoln, Sept. 28, 1863).

Unlike the other Presidents, Lincoln took her letter to heart. On October 23, 1863, just a week after he received her letter, President Lincoln signed a proclamation designating the last Thursday of November as a National Day of Thanksgiving, establishing its national observance. The text, written by Secretary of State Seward, explicitly requested that Americans implore God to "heal the wounds of the nation and to restore it...to the full enjoyment of peace, harmony, tranquility and Union". This proclamation has been cited as the precedent for the modern national holiday. Lincoln often attributed Sarah Hale's letter as a main factor in this decision. Ever since then, there has been a nationwide celebration of Thanksgiving at the end of November. And, it is still celebrated in much the same way as it was described in "Northwood: Life North and South" 200 years ago.

The Rest of the Story

Sarah Josepha Buell Hale (Oct. 24, 1788 – April 30, 1879) known for her poem "Mary Had a Little Lamb", was born in Newport, NH to very progressive parents who encouraged her to continuously self-educate. She married lawyer David Hale in 1813 and had 5 children. Sadly, the oldest died at 7. Shortly afterward she was widowed. As a symbol of perpetual mourning, she wore black for the rest of her life. She turned to poetry and then novels as a form of income, before becoming editor of "Godey’s Lady’s Book" , a position she held for over 40 years, retiring in 1877. By the time of her death, she had published over fifty volumes of works. Besides her writing, she was instrumental in the completion of the Bunker Hill Monument and the preservation of Mount Vernon. An early advocate of women’s higher education, she helped found Vassar College and the Baltimore Female College. She was a strong abolitionist and advocated for the American union. She supported many women's rights issues, but surprisingly not suffrage. Instead, she believed in the “secret, silent influence of women” to sway male voters. She is buried in Philadelphia at the Laurel Hill Cemetery.